Working Upstream to Enrich Veteran Wellness and Prevent Suicide

Photo by Holly Mindrup on Unsplash

Author: Omkar Ratnaparkhi

This story is the first in a series about how The MITRE Corporation tackles complex problems. This first article probes the concept of upstream thinking in the context of veteran wellness and the value of designing with people rather than for them. A story on the upstream value of using artificial intelligence to model COVID-19 data will follow. Stories on how MITRE’s student research programs develop researchers who want to work in the public interest will round out the series.

The ACE Card

One Wednesday afternoon this past February, everyone in my Army Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) military science class at Fordham University received a card embossed with an ace of hearts. The back of the card read Army Strong and ACE Suicide Prevention, breaking down the acronym to Ask your buddy, Care for your buddy, and Escort your buddy. Each description included techniques and resources for preventing a suicide: Stay calm, remove means of self-injury, and escort your friend to the chain of command or chaplain. Sobering information for a 19-year-old cadet like myself.

Although I didn’t realize at the time, the ACE card and the time of its distribution represent both upstream and downstream thinking, the value of which I now understand.

Preventing Problems Instead of Reacting to Them

When an individual identifies ways to stop problems from developing into crises, they are thinking upstream, according to Dan Heath’s 2019 book Upstream. In contrast, downstream thinking occurs when people react at the time of crisis, without having been able to head off the problem earlier.

The actions listed on the ACE card work downstream because they explain how to stop a member of the armed forces from committing suicide after they have already contemplated and exhibited the behaviors of self-harm.

My military science instructor explained that basic training required drill sergeants to distribute ACE cards to privates—or, in my case, a freshman Army ROTC cadet—as a first step in learning what to do if we saw fellow soldiers displaying acute mental distress. The decision to distribute the ACE cards to new recruits right away was an upstream solution, as essential to saving lives as the information itself.

As an Army ROTC cadet, I will commission into the US Army as an officer upon graduation, and I will most likely be a platoon leader with responsibility for 20-50 soldiers. It concerns me that individuals under my command might contemplate suicide, so I chose to spend part of my summer internship investigating one MITRE team’s upstream approach to reducing veteran suicide: enriching veteran wellness.

The Leverage Point for Veterans: Transitioning to the Civilian World

As I was introduced to MITRE’s work on behalf of veterans, I learned some disturbing statistics. According to the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), 22 veterans take their lives each day in America. Many veterans are even taking their lives in the parking lots of VA hospitals. Veteran mental health is such a complex issue that the crisis in this area has persisted despite the most compassionate efforts of the VA, Department of Defense, and other government agencies.

Discovering that veterans’ wellbeing is a priority issue for MITRE, too, I had the privilege of interviewing the Principal Investigator for the Design for Life MITRE Innovation Project on veteran mental health, Awais Sheikh. In addition to pointing me to Heath’s book, Awais explained the link between his team’s earlier research on preventing veteran suicide and their current focus on wellness. “We researched and conducted literature reviews on transition and then reached out to veterans and tried to see what aspects of our research resonated with their experiences,” he told me. The team came to realize, in fact, that to make an impact in preventing suicide, they needed to start working upstream on wellness—with veterans—both before and after transition, instead of waiting until veterans were considering suicide.

Why? Because transition is a leverage point in a veteran’s life. Heath defines leverage points as small interventions that can lead to big changes. According to MITRE Senior Health Systems Analyst Rachel Mayer, who consulted on Design for Life, “Most veterans commit suicide within one year of transitioning to the civilian world.” Thus, the upstream leverage points are the year before and the year after leaving the military. She reports that, in response, the VA has set up a program called Solid Start, based on MITRE research. Program staff call veterans three times during the year after they leave the military and educate them on VA benefits and programs. If a veteran seems to be at risk of suicide during one of these calls, they are forwarded to a suicide crisis line. And, yet, this intervention remains insufficient, suggesting that at least one additional factor is salient.

Social Connectedness as Part of the Upstream Solution

The military gives veterans structure and camaraderie that the civilian world rarely replicates, and the absence of that structure during transition is affecting the current generation of veterans. According to the VA’s National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide, recently transitioned veterans ages 18-39 commit suicide at higher rates compared to older veterans. Although combat casualties have decreased, younger veterans have served more time overseas and away from their families than did previous generations. These younger veterans feel as though they have left their tribe when they leave the military, perhaps because they came of age while in the military. With limited experience in the civilian world and long periods away from their families, re-connecting with life back home is challenging. They’ve expressed a need for ways to develop and sustain social connectedness—during their service, during transition, and as they continue in civilian life.

Among the veterans groups with whom the research team spoke to explore the need for social connectedness were MITRE’s own Veterans Council, The Mission Continues, and Team Red White and Blue. After capturing a diverse set of experiences from the participants, the team noticed common trends. For example, Servicemembers had all had multiple awkward and alienating social interactions with non-veteran civilians. According to Ben Mayer, a Domain Analyst on the Design for Life team, “Many veterans felt that saying ‘thank you for your service’ was a way to show appreciation for their sacrifices and the sacrifices of their family; but on the other hand, in many ways, it felt like a throw-away statement that wasn’t disingenuous, but it did distance veterans from others.”

How, then, could the researchers close that distance?

A Framework for a Better Future

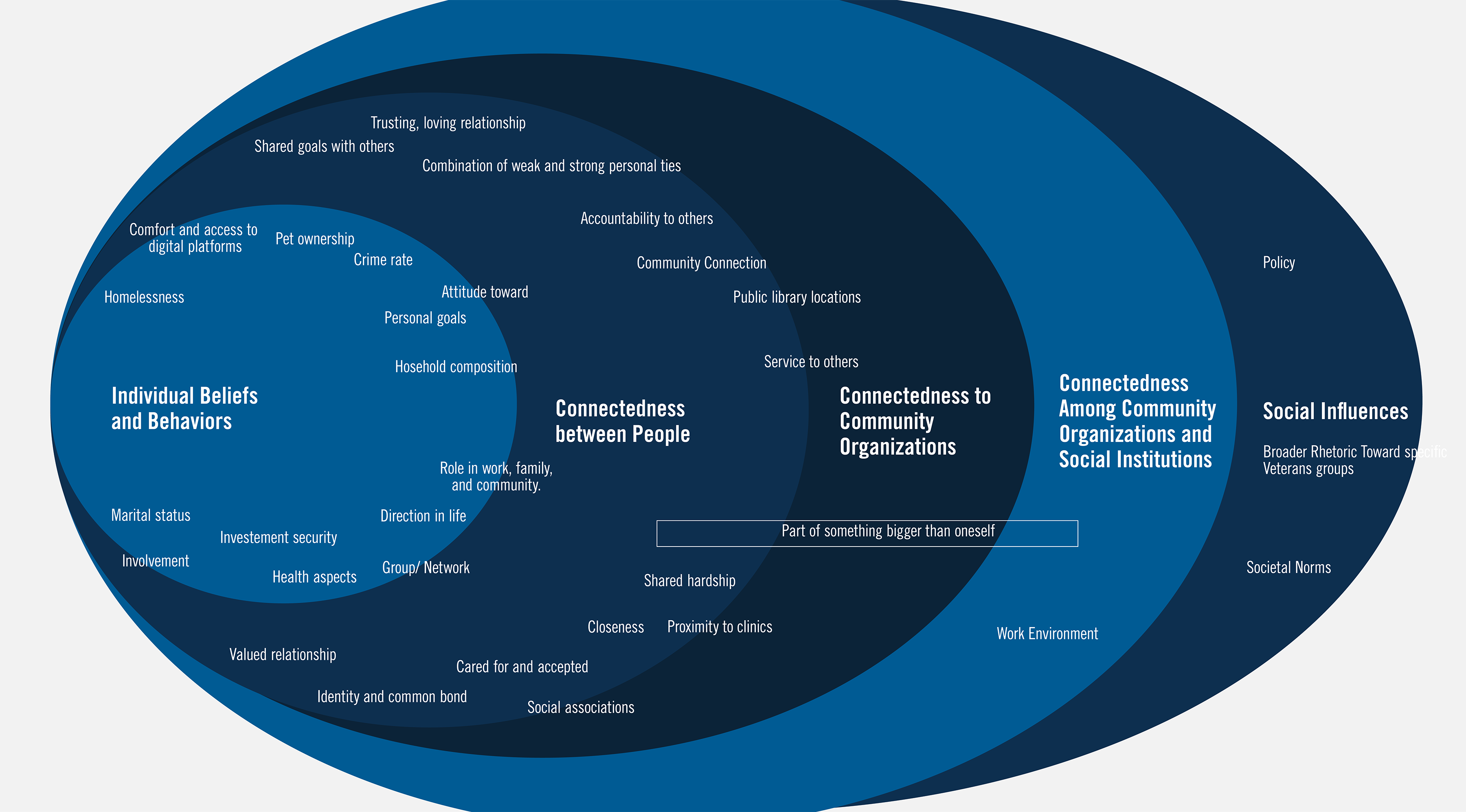

The Design for Life team wanted to prototype a service that the VA could use to help veterans sustain connections that are meaningful to them. To that end, they created a Conceptual Framework for Servicemember Social Connectedness, based on the team’s literature review, loneliness risk predictors, and models from veteran-serving organizations. Government organizations such as the VA’s Office of Transition and Economic Development might leverage the model to help veterans find structure and connectedness. Pathways could range from finding meaningful employment to finding structure in life through hobbies like cooking, to finding ways to serve their communities alongside other veterans.

The Design for Life Conceptual Framework for Servicemember Social Connectedness

Click to enlarge

The Design for Life team hopes to build on the framework, and to transition it to additional organizations. In so doing, they aim to help transitioning veterans feel well, stay well, and do well for the rest of their lives.

Omkar Ratnaparkhi is Summer Student Investigator in the Emerging Technologies Department at MITRE. He is engaged in public-interest reporting on leading-edge problem-solving approaches and technologies. A rising sophomore at Fordham University and a cadet in Fordham’s ROTC program, he is majoring in International Political Economy, and plans to attend law school.

© 2020 The MITRE Corporation. All rights reserved. Approved for public release. Distribution unlimited. Case number 20-1962

MITRE’s mission-driven teams are dedicated to solving problems for a safer world. Through our public-private partnerships and federally funded R&D centers, we work across government and in partnership with industry to tackle challenges to the safety, stability, and well-being of our nation. Learn more about MITRE.

See also:

MITRE Innovation Program Team Hosts Design Studio on Veteran Mental Health with MITRE Veterans

Military to MITRE: Perspectives of Recently Transitioned Veterans

Improve Your Resiliency Without Wearing Camouflage

Using Artificial Intelligence to Improve Health Outcomes for Veterans

When AI and Psychology Meet, Insights Emerge

Designing a Bridge Between Theory and Practice

Interview with Awais Sheikh on Deciphering Business Process Innovation

Preparing for the Future by Knowing How to Take a Punch

Getting Students Excited About STEM (and MITRE), with Willie Hill

The Emerging Technology Student Program’s New Frontier

Many Heads Are Always Better Than One

Changing Organizations Using the Power of Localism

Mistakes and Transcendent Paradoxes: Dr. Peter Senge Talks on Cultivating Learning Organizations