MITRE Innovation Program Team Hosts Design Studio on Veteran Mental Health with MITRE Veterans

Author: Colin Raunig

As part of their research into veteran mental health, MITRE Veterans Council members and the Design for Life MITRE Innovation Program research team hosted a design studio dedicated to hearing directly from veterans about their transition from active duty to civilian life.

Cassie Browning, Cynthia Gilmer, Ben Mayer, and Awais Sheikh implemented a strategy known as design thinking, also called human-centered design, which is an innovative problem solving process largely used for wicked problems. Wicked problems have innumerable causes, are tough to describe, and don’t have a right answer. Design thinking began gaining traction in 2008 and has been used since then to help teams or organizations facing difficult and ambiguous situations to develop a wide range of products and services, from creating a business model for selling solar panels in Africa to the operation of Airbnb.

In this case, the Design for Life team used the design thinking approach to learn more about veteran transition, and to do so by learning from veterans themselves. They decided to host a four-hour session during which they would invite and speak with veterans. Almost 30% of MITRE employees are veterans, so when the team wanted to have preliminary conversations with veterans who had already transitioned successfully, they had access to the right people.

“We were thinking of problems that could benefit from design thinking,” Awais said, explaining why they chose this approach. “Veteran mental health and suicide prevention seemed to take a top clinical priority.”

Indeed they do. Veteran mental health care is in a state of national crisis. In April 2019, a veteran committed suicide outside the Department of Veteran Affairs Medical Center in Cleveland, which was the seventh suicide on VA property this year. Each day 20 veterans and service members, to include reservists, and members of the National Guard, die by suicide. Risk of suicide is 1.5 times greater for veterans as compared to civilians after adjusting for age and gender.

Something new is required to help veterans, and the team thought that design thinking might help find a solution. The goal was to learn about issues that aren’t immediately visible. The research team found in their literature review that some veterans had a lot of underlying stress factors that were not “readily available on the surface,” according to Ben.

“The whole point is to put the people who have the problem at the center of the process and try to understand their perspective for the problem and the solution,” Cynthia said.

Going into the session, the team developed two hypotheses in relation to veteran mental health stressors: transition and connectedness. The team theorized that the transition from active duty to veteran status is stressful and that once they have transitioned, it is difficult for veterans to connect with other civilians due to differences in background and experience. Whether or not these hypotheses were true would indicate what the proper response should be.

The team hosted a four-hour session, inviting 10 MITRE veterans. The first half of the session was dedicated to gathering and listening to veterans’ personal stories. From these stories, the team learned that a large part of the veteran transition process occurs before they leave the military, while they are still active duty.

“It’s a period where service members don’t get a lot of support, but should,” Ben said, adding that support is needed for PTSD and how to function in society without the military as support.

“By identifying where the gaps are, the team would be able to understand what the solutions should be,” he added.

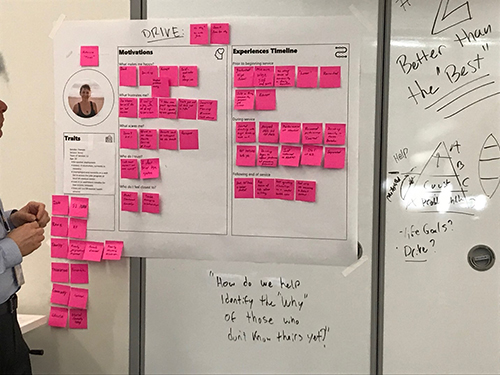

For the second half, the Design for Life team used a more dynamic approach. They created three archetypes, or personas. These personas were fictional characters. One persona was a man in his mid-60s from the Vietnam-era, but who never deployed. Another was a man in his late twenties who served in Iraq as a Marine. The third was a woman in her early twenties who was less than honorably discharged from the Army after a deployment in Korea.

These personas were not pre-generated. During the session, the veterans self-selected which character they wanted to contribute to, and in each group, they worked together on filling out the blank template of motivations and experiences based on their respective picture and biography. As they generated their personas, participants uncovered underlying risk factors for suicide. Being a loner was the most common trait. In other cases, the characters didn’t really have a sense of identity outside the military, or they came from a troubled background, and felt that asking for help was a sign of weakness.

Although the team had primed the veteran participants in the design studio with the knowledge that each character was a suicide risk, in the templates filled out, combat experience came up only once. This went against the notion that combat is a predominant factor for veteran suicide risk. The created characters demonstrated moderate, not high, suicide risk.

Overall, the session was a success.

“The veterans were able to leverage a lot of different experiences and backgrounds,” said Cassie, Co-Chair of the MITRE Veterans Council.

“It exceeded our expectations,” Cynthia said, crediting the participatory atmosphere from the veterans and the comfortable and safe atmosphere that the facilitators were able to cultivate. “It was really good, and they shared things that were personal and emotional. There were many “ahas” in it for me.”

An example of one of these “aha” moments, which illuminated information that Cynthia hadn’t previously realized, is how veterans gravitate towards a structured environment after they leave the military, and the positive impact this environment can have on their lives and the lives of their families. Ben also noted that veterans like activities similar to ones they had in the military, and that finding these activities helped to ease their transition. These activities included ones that were mission-driven, team-based, and outdoorsy.

This knowledge gathered during the session will help the Design for Life team determine whom to reach out to and how. They have refined their hypotheses and want to scale out what they have learned with a more representative data set. Their next step is to reach out to organizations, including NGOs and veteran nonprofits, to identify which veterans they should be targeting as well as risk factors not identified by the VA. Then, the team will try to prototype some kind of service.

The team is working to identify a focus area of future exploration based on the session they had. Awais spoke to the need for “connectedness in the moment.”

“Not just problem exploration,” Awais said. “But solution exploration and prototyping as well.”

Colin Raunig is a Senior Business Strategy Analyst at MITRE. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Colorado State University and a BS in Ocean Engineering from the United States Naval Academy. He served for eight years active duty and three years reserves as a Naval Flight Officer.

© 2019 The MITRE Corporation. All rights reserved. Approved for public release. Distribution unlimited. Case number 19-2476.

MITRE’s mission-driven team is dedicated to solving problems for a safer world. Learn more about MITRE.

See also:

Military to MITRE: Perspectives of Recently Transitioned Veterans

Getting the Most out of Your Failures

The Lunch and Learn is not the Solution to Everything

Beware of Low-Hanging Fruit

Changing Organizations Using the Power of Localism

Communication—the Special Sauce of Major Change

Mistakes and Transcendent Paradoxes: Dr. Peter Senge Talks on Cultivating Learning Organizations

Naming the Elephant in the Room