A Story of the Game-Changing Value of Tacit Knowledge: “Is There a Doctor in the House?”

Photo by JC Gellidon on Unsplash

Author: Marshall Maglothin

MITRE is often brought in to help solve hard science problems for Federal agencies, including adoption of emerging technologies like Blockchain or artificial intelligence solutions, and tackling complex problems in cybersecurity and engineering. We’re also brought in to help with solving problems in some of the so-called softer sciences, such as planning and transitioning Federal agencies to innovative IT frameworks and technology solutions or supporting communication channels and new process infrastructure that enable the enterprise’s workforce to adopt innovative solutions.

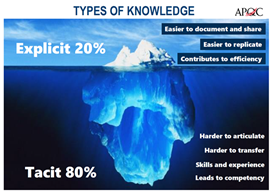

In a similar way, MITRE’s talents for strategic modernization (e.g., enterprise planning, organizational change, business innovation, technology transitioning) are informed by both our explicit knowledge and our tacit knowledge. Explicit knowledge is what we objectively know. Explicit knowledge can be readily articulated, codified, stored and accessed, and transmitted to others, and represents an estimated 20% of our knowledge (e.g., plans, reports, data analysis). Implicit or tacit knowledge is more subjective. It comes from personal experience, which can be up to 80% of our knowledge (e.g., problem-solving, expertise, models, best practices, intuition). Tacit knowledge enables the breadth of MITRE’s experiences across multiple Federal agencies to serve as a force multiplier of MITRE’s strengths in the explicit harder sciences.

The following parable aims to illustrate the value of both explicit and tacit knowledge and the roles they play in critical strategic enterprise planning and decision processes.

Snapshot of Collaboration

It was 9:30 pm. They were bone tired. And they all just wanted to go home.

The 14 people around the conference table were the elected Board of The Heart Specialists, a private practice of 40 physicians and over 180 support employees. For the past two-and-a-half hours, they had been discussing the dream keeping them in the meeting: their plans to move from their various rented offices into a consolidated $15M clinic they would build and that would also house the latest health technology (expensive cardiac diagnostic equipment and an Electronic Health Record software system).

A medical emergency intervened, however, and a 15th member of their team (Sarah, an interventional cardiologist) had received a page a half hour ago and left to rush to a hospital to possibly implant a stent in a cardiac patient. It was rare that none of the others on the board had been called away, and they had been able to attend all of this critical business meeting.

One of the board members asked, “Why don’t we just wait until next month and take a vote?” As if on cue, his pager erupted. He stepped into the hall, but in less than a minute returned and remarked, “Just a med increase request from General’s Cardiac Care Unit.”

Explicit Knowledge at Work

Jim, the president of the group said, “I don’t think we are ready to vote at this moment. But we do need to decide tonight because our new office planning is at the point where the architect must know if we are going to install that major piece of new equipment. We each have a notebook of long-range demand projections, financial pro formas, plans, calculations of our current capacity and future growth, and equipment ROI calculations. Let’s call this notebook our “Explicit Knowledge Planning Bible.”

Ashesh, a physician partner and long-time friend of Jim’s, couldn’t help but smile when Jim mentioned “explicit knowledge.” Indeed, their notebooks were classic examples of explicit knowledge: documents, data, monthly reports, and calculations that were easy to duplicate, share, reference and re-evaluate. Ashesh now knew the direction the meeting would take, and that it was actually possible that a unanimous decision would be reached by 10:00 pm. This was because the group not only had the notebooks of all the required explicit material; the members of the board also possessed a deeper, richer tacit knowledge of their group practice that Jim would now ask them to express.

Ashesh, a physician partner and long-time friend of Jim’s, couldn’t help but smile when Jim mentioned “explicit knowledge.” Indeed, their notebooks were classic examples of explicit knowledge: documents, data, monthly reports, and calculations that were easy to duplicate, share, reference and re-evaluate. Ashesh now knew the direction the meeting would take, and that it was actually possible that a unanimous decision would be reached by 10:00 pm. This was because the group not only had the notebooks of all the required explicit material; the members of the board also possessed a deeper, richer tacit knowledge of their group practice that Jim would now ask them to express.

Technical Tacit Knowledge as a Force Multiplier

Jim said “Let’s talk about what lies behind these reports. Harvey, during undergrad at Stanford, along with biology, you majored in accounting. What’s your take on the numbers used for these projections?”

Harvey, who had not yet had much to say, replied, “Well, we’re all equal partners in this practice. Like the rest of you I have a significant financial risk in this. A new four-story building, its equipment, and a regional enterprise EHR (electronic health record) are something I never thought we would attempt as individual projects, much less at the same time. But I have examined and dissected our Knowledge Bible multiple times, and I see no apparent weaknesses. Our new equipment will address a number of our inefficiency issues, and moving from a single paper chart to EHR will finally provide us our patient records not only in our office, but also when we are at home or even 100 miles away at a community hospital weekly clinic. And, tonight’s in-depth discussion has pulled together the deep experience of not only how we provide care individually, but also how we collaborate and support each other as a group practice.

As Harvey spoke, most of the others around the table seemed to relax a little and, perhaps unconsciously, nod their heads slightly. Harvey had not only confirmed the notebook’s explicit numbers but had also delineated for the group its technical tacit knowledge: their passionate exchanges during the meeting communicated what numbers in their binder ‘bibles’ could not—their decades of committed patient care experience, expertise, and skills.

Jim asked, “Does anyone see any gaps in the information that we still need or contradictions to Harvey’s conclusions?” No one responded, but the group still did not seem eager to press forward.

“We think we have all the information we need,” Jim continued, “and we have developed it and evaluated it for months. From our tacit technical collective experience and understanding, we have shared that we think our conclusions are valid. So, let’s explore why we still seem to be less than enthusiastic.”

Cognitive Tacit Knowledge as Leverage for Decisive Decision-Making

Ashesh was first to speak, “On a deeper level then even our professional experiences, I think we have developed solutions that we intuitively believe will support us in continuing to achieve the best outcomes, both for our patients and our business. But we haven’t really discussed another deep consideration: the emotional aspects of committing to these plans. Yes, our plans are fact-driven, but they don’t just provide new tools; they represent a significant restructuring of our professional lives. And, we aren’t just manufacturing widgets. We are impacting our entire region of over 20 hospitals and impacting patients who have chronic cardiac disease and in many cases are also our friends, neighbors, and even family.

“For me,” Ashesh continued, “our offices are spread out, but my individual route to my office and my relationships with the small number of staff there are familiar, so consolidating into a single building will be a big change me as well as for all of us. I guess a good analogy would be that it’s like buying a new home, which is exciting, but also entails your family leaving the old one and its routines and cherished memories.”

For the next 15 minutes, the board talked about the deeper tacit knowledge aspects of the decision: their various viewpoints of the coming practice modernization, the aspects of their routines that would have to change, their mental models of what an essentially new practice would look like, and, most importantly, their emotions about all these factors.

Jim then said, “Karen, you’ve been very quiet. Can you share with us your thoughts?

Karen spoke slowly, but with a positive note in her voice. “As you know, Jim and I started this practice 22 years ago. And it has been everything I had hoped for. Now, we are talking about new directions. My deep emotional investment, my understanding of our collective vision and commitment, and my basic Spidey-sense intuition say we are all primarily here to serve our patients. I believe this new office, its equipment, and our EHR will position us to continue to provide the highest quality heart care for our region and a professional platform for ourselves for at least the next two decades. Jim, I move we proceed with all due haste and enthusiasm!”

The motion was seconded and passed unanimously.

Just then, Sarah re-entered the room. “The patient turned out not to need the cath lab. It looks like there’s a lull in our planning discussion. I had time in the car to think. Yes, I’m dreading all the changes, but I am very excited about our plans! My experience in this community and my instincts tell me this is the right thing and the time is now. When do we vote?”

Ashesh looked at Jim with a big grin and said, “And that, Ladies and Gentlemen, makes the vote unanimous and 100%. The time is 9:59. Can we please go home now?”

A Way Forward

Like this medical group, government agencies are facing multiple strategic challenges, but on a national scale. MITRE subject matter experts provide explicit knowledge to help anticipate and respond to these complex organizational issues: strategic management, governance, and decision making; business innovation and design; organization development, stakeholder engagement, and communication; and enterprise transition planning, architecture, and shared services.

Agencies have existing, full, and complex daily workloads required by their operations. MITRE offers additional agile engineering and bandwidth to help manage extensive change while maintaining mission-critical operations. A way forward is informed and proposed by tapping into the deep technical and cognitive knowledge of the agency workforce and by being informed by the knowledge base of MITRE’s multiple Federally Funded Research and Development Centers.

MITRE scales its approach to agency collaboration by fitting the need and required capabilities of project teams for each engagement. MITRE then helps integrate existing initiatives— technology modernization, employee and stakeholder engagement, and process innovation— to make the organization more agile, efficient, and effective: To solve problems for a safer world.

Marshall Maglothin is a business systems innovation engineer at MITRE. He specializes in process and quality improvement and in strategic organizational transitions. He holds an MHA in statistics and operations from the School of Public Health of the University of Minnesota, and an MBA in finance from the Carlson School of Management of the University of Minnesota.

See also:

Avoiding Single Points of Failure Through Knowledge Sharing

When AI and Psychology Meet, Insights Emerge

An Introduction to Interoperability in Healthcare

Framing Ethical Standards for Data Use in Health Care

The Person at the Other End of the Data

© 2020 The MITRE Corporation. All rights reserved. Approved for public release. Distribution unlimited. Case number 20-0788.

MITRE’s mission-driven team is dedicated to solving problems for a safer world. Learn more about MITRE